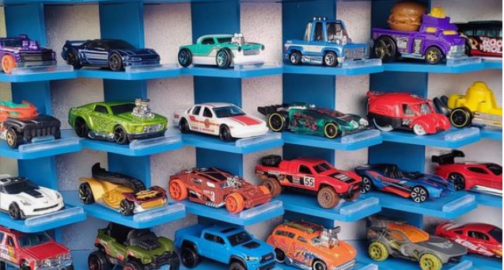

“The disease has metastasized,” Bruce Pascal says as we enter a former fabric warehouse in the Washington, D.C., suburbs, which he has christened the East Coast Hot Wheels Museum. A couple of years ago, Pascal decided that his Hot Wheels collection needed more space—it was already massive when we first met him at a convention oflike-minded obsessives while researching a C/D story.

The trophy room that Pascal had designed at his Maryland home included a desk with drawers for thousands of the little cars, storage and display shelving along the walls for original design drawings, and a stylized version of the brand’s iconic orange track zooming up the walls and ceiling, framing Hot Wheels ephemera. But it was starting to feel a bit constrained, given the size and scale of some of his new purchases. Hence the new 4000-square-foot home for the world’s most valuable Hot Wheels collection.

He sets down a stack of recent acquisitions in what he calls the Intake Room. They include giant plastic sleeves holding Hot Wheels engineering blueprints, a rolled-up eight-foot-long promotional Hot Wheels poster, and flattened cardboard vintage Hot Wheels store displays, all recent purchases from the two hours he says he spends daily conducting online searches and following up on leads.

“It’s definitely getting more difficult to segregate my daytime and nighttime jobs,” he says. “The hobby is taking over.”

Pascal is a commercial real estate broker—which surely came in handy when he decided to acquire a big building—but his penchant for vehicular accumulation comes naturally. His grandfather was an automotive historian employed by the National Archives, and his father was active in the Rolls-Royce Owners’ Club of America. Pascal himself was always a collector, previously assembling (and then selling) a stockpile of objects related to the Tucker car company and a comprehensive assortment of political buttons. But after his mom gave him back his childhood collection of Hot Wheels cars 15 years ago, he has remained laser focused on the brand.

The other half of the collection is ephemera and paraphernalia. There are dozens of vintage play sets, carrying cases, and accessories. There are store displays, promotional posters, sales brochures, and salesmen’s cases. There are Hot Wheels racks from Germany and Japan. There is a confounding array of Hot Wheels–branded products: wallets, chewing gum, patches, shampoo, puzzles, pins, comic books, race suits, jeans, tattoos, baseball hats, and stickers. There is even a Hot Wheels vinyl record, the soundtrack to an animated Saturday morning cartoon series that aired on ABC from 1969 to 1971. “It’s not cool music,” Pascal says. “You do not want to listen to it.”

Pascal’s latest obsession is in works on paper: original drawings, documents, and artwork related to the brand. He has uncovered technical blueprints, competitive intelligence reports, patent applications, even “ideas memos” submitted by Mattel employees for unimagined (and sometimes unimaginable) product extensions.

But his greatest affection seems reserved for the promotional artwork created by Otto Kuhni, a freelance graphic designer who was responsible for creating the original Hot Wheels packaging, used for the cars, playsets, and dozens of other artifacts. Before Kuhni passed away in 2017, Pascal commissioned him to create signature overarticulated space-age paintings of some of the vehicles in his collection. After Kuhni died, Pascal bought dozens of original works from his estate—sketches, drawings, illustrations, proofs. Some of it hangs, in orange-track-colored frames, on the museum’s walls.

Pascal says he hopes to open the space to the public eventually, and he is working with an architect to come up with a design that maximizes impact.

“Ninety-nine percent of collectors display their collections the way Safeway displays its food,” he says. “When you go to the Louvre, you see the Mona Lisa alone on the wall. I want it to feel more like that.”

Before he can welcome the masses to his museum, however, he has to figure out a means of securing his objects. “I want to make sure that my collection of 3500 cars doesn’t become a collection of 3000 cars or 2000 cars.”

Now that he’s in his late fifties, he also has to think about his legacy. His wife has been a willing partner in allowing him to acquire, to fulfill his dreams. But she does have one stipulation. “Her only request,” he says, “is that I don’t pass away before I get rid of the collection.”