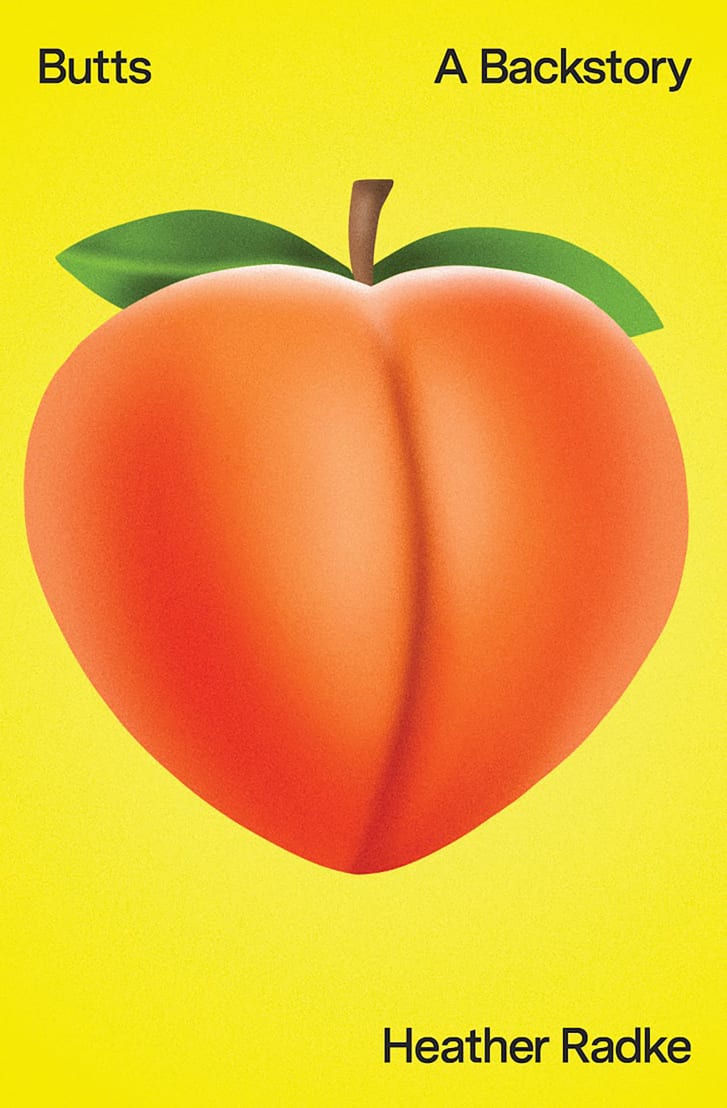

In the introduction to her book “Butts: A Backstory,” journalist Heather Radke recalls a moment when, at 10 years old, she and a friend were cat-called by two teenage boys while out riding their bikes.

“‘Nice butts!’ we heard them say,” Radke writes. “The fact that they said something unprompted about our butts felt uncomfortable and bizarre… I was aware that there were body parts that were considered beautiful and sexy and were coveted by others, but it had not occurred to me that the butt was one of them.”

That episode was just one a series that led Radke to realize how big of a role backsides play not just in our relationships with our bodies, but in the cultural, social and gender-specific experiences that define womanhood.

“Butts, silly as they may often seem, are tremendously complex symbols, fraught with significance and nuance, laden with humor and sex, shame and history,” she writes. “The shape and size of a woman’s butt has long been a perceived indicator of her very nature — her morality, her femininity and even her humanity.”

It’s from these observations that “Butts” — a thoroughly researched cultural history of the female butt — stems.

From supersized to a more natural look: The evolution of breast implants

Weaving together memoir, science, history and cultural criticism, the book addresses the physiological origins of our behinds and takes readers from the cinched waists of the Victorian era all the way to Kim Kardashian’s Internet-breaking backside and the popularization of the Brazilian butt lift. In between, Radke examines the role of eugenics, fashion, fitness fads and pop culture in defining the racial and misogynistic standards surrounding the butt.

“I only know what it’s like to be a White woman with a big butt, which obviously has its limitations,” Radke said in a phone interview. “It was important to me to challenge our ideas about where bodies come from by listening to different voices.”

“Since the rise of the transatlantic slave trade, there’s always been a kind of racial undermeaning in any conversation around the butt, as well as gendered approaches to questions like ‘What is a feminine body? What is a beautiful body? And how feminine can a beautiful body be?'” she continued. “The answers to those questions have oscillated through time, but our deep preoccupation with this specific body part reveals how the butt has long been used as a means to impart control, prescribe desire, and install racial hierarchies.”

Butt-based prejudice and appropriation

A recurring figure in “Butts” is Saartjie “Sarah” Baartman — the so-called Hottentot Venus (the term Hottentot, now widely regarded as offensive, was historically used to refer to the Khoekhoe, an indigenous tribe of South Africa). Baartman was an Indigenous Khoe woman forced to exhibit her “large butt” for White audiences in Cape Town, London and Paris in the 19th century.

Radke’s account of Baartman’s life, and of how her body became “a fantasy of African hypersexuality,” underlies much of the book’s narrative, as she traces the stereotypes created by European “racial scientists” of that era and, later, the skewed and prejudiced legacy of big-butted women as more highly sexual — especially Black women — directly back to the exploited Baartman.

Radke spoke with Janell Hobson, a professor of women’s, gender, and sexuality studies at the State University of New York at Albany who has written extensively on Baartman. Hobson links the fetishization of Baartman’s figure to the seeding of colonialism and the continuation of slavery into White society.

‘Calendar Girls’ shows senior women like you’ve never seen them (but probably should)

“(Baartman’s) show perpetuated ideas around African savagery and primitive Black womanhood, ” Hobson explains in in the book. “So when white people were looking at Sarah Baartman, they were projecting all of this stuff they’d already inculcated in the culture.”

“Baartman’s story is still with us in a lot of ways,” Radke said. Although she died in 1815, “her body was on display in Paris up until the 1980s, then again in the ’90s. That really isn’t that long ago, and tells you just how much we’ve turned her into something grotesque to gawk at — a stereotype and symbol of exploitation.”

Radke later points to the bustle — an undergarment popularized in the late 19th century designed to make a woman’s backside look enormous — as a glaring example of White appropriation of Baartman’s figure. “It was a way for Victorian women to look like Sarah Baartman, while at the same time asserting their own whiteness and privilege, as it could simply be taken off,” Radke said. “That behavior would be repeated again and again through history.”

Shee explores that same butt-based cultural appropriation — and monetization — as exercised by celebrities like Kim Kardashian and Miley Cyrus, whose famous twerking routine at the 2013 MTV Video Music Awards and during concerts on her “Bangerz Tour” that same year (where she used a large prosthetic butt as part of her choreography) was, Radke writes, a prop to “‘play’ in Blackness.”

The ‘fox eye’ beauty trend continues to spread online. But critics insist it’s racist

Alongside addressing the visual culture of Black music videos, plastic surgery and the recent belfie (a portmanteau of butt and selfie) craze in the same vein, Radke also highlights periods in contemporary history where trends skewed in different, oppositional directions. She highlights the rise of “buttless women” in the 1910s — a look best represented by the sleek look of the flapper — through the invention of sizing and the 90s brand of “heroin chic” captured by the supermodel Kate Moss. Such an aesthetic is “something that’s never really gone away,” Radke noted.

“I didn’t aspire to write an encyclopedia of the butt, but rather give a historical context to the way it has been perceived and portrayed, and how women’s feelings around it have shifted alongside it,” Radke explained. “Whether consciously or not, we, and society at large, have always been paying attention to our butts — hiding them, accentuating them, fetishizing them. Which is kind of funny, when you think it’s actually a body part we cannot see ourselves unless we’re in front of a mirror.” As she writes in her book, “the butt belongs to the viewer more than the viewed.”

Reclaiming the butt

While many of the stories exposed in “Butts” are steeped in physical suffering — diets, restricting shapewear, surgical scalpels — there’s also joy to be found.

To counter the extreme workout regimes of the 80s, like the “Buns of Steel” fitness craze that equated a sculpted butt to self-control and self-respect, Radke profiled the fat fitness movement that emerged during the same decade, which reimagined “what was possible for people who often felt excluded from mainstream fitness culture” to offer a form of resistance.

In Astoria, Queens, she spent time with a group of drag queens who sculpt foam butt pads to embellish their backsides, turning the butt into something joyous and judgment-free.

“A history of bodies — especially female bodies — is always going to be a history of control and oppression, but I felt it was important to also show the other possibility: liberation,” Radke said. “Those stories were some of the most fun research I did, and some of the most surprising, too, as they allowed me to meet people who have overcome societal prescriptions, and embraced a different way to think about bigness, which helped me reframe it, too.”

Ultimately, Radke said, what’s perhaps most compelling about the butt is that it doesn’t have to mean anything.

“Butts have the power to make us feel so miserable or angry, especially when we’re in a dressing room trying on a pair of jeans that just won’t fit,” she noted. “But that angst is the result of centuries of history, culture and politics. It doesn’t come from our bodies, it has been placed on them. If we take a step back, we’ll see that butts are just a body part. They could mean nothing at all.”